CORONA VIRUS

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans, these viruses cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses include some cases of the common cold (which is caused also by certain other viruses, predominantly rhinoviruses), while more lethal varieties can cause SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. Symptoms in other species vary: in chickens, they cause an upper respiratory tract disease, while in cows and pigs they cause diarrhea. There are as yet no vaccines or antiviral drugs to prevent or treat human coronavirus infections.

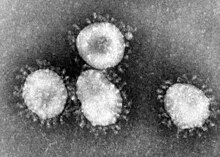

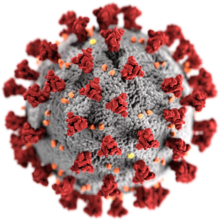

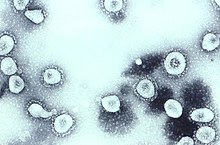

Coronaviruses constitute the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae, in the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, and realm Riboviria.[5][6] They are enveloped viruses with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome and a nucleocapsid of helical symmetry.[7] This is wrapped in a icosahedral protein shell.[8] The genome size of coronaviruses ranges from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases, one of the largest among RNA viruses.[9] They have characteristic club-shaped spikes that project from their surface, which in electron micrographs create an image reminiscent of the solar corona, from which their name derives.[10]

Etymology

The name "coronavirus" is derived from Latin corona, meaning "crown" or "wreath", itself a borrowing from Greek κορώνη korṓnē, "garland, wreath".[11][12] The name was coined by June Almeida and David Tyrrell who first observed and studied human coronaviruses.[13] The word was first used in print in 1968 by an informal group of virologists in the journal Nature to designate the new family of viruses.[10] The name refers to the characteristic appearance of virions (the infective form of the virus) by electron microscopy, which have a fringe of large, bulbous surface projections creating an image reminiscent of the solar corona or halo.[10][13] This morphology is created by the viral spike peplomers, which are proteins on the surface of the virus.[14]

History

Coronaviruses were first discovered in the 1930s when an acute respiratory infection of domesticated chickens was shown to be caused by infectious bronchitis virus (IBV).[15] Arthur Schalk and M.C. Hawn described in 1931 a new respiratory infection of chickens in North Dakota. The infection of new-born chicks was characterized by gasping and listlessness. The chicks' mortality rate was 40–90%.[16] Fred Beaudette and Charles Hudson six years later successfully isolated and cultivated the infectious bronchitis virus which caused the disease.[17] In the 1940s, two more animal coronaviruses, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), were isolated.[18] It was not realized at the time that these three different viruses were related.[19]

Human coronaviruses were discovered in the 1960s.[20][21] They were isolated using two different methods in the United Kingdom and the United States.[22] E.C. Kendall, Malcom Byone, and David Tyrrell working at the Common Cold Unit of the British Medical Research Council in 1960 isolated from a boy a novel common cold virus B814.[23][24][25] The virus was not able to be cultivated using standard techniques which had successfully cultivated rhinoviruses, adenoviruses and other known common cold viruses. In 1965, Tyrrell and Byone successfully cultivated the novel virus by serially passing it through organ culture of human embryonic trachea.[26] The new cultivating method was introduced to the lab by Bertil Hoorn.[27] The isolated virus when intranasally inoculated into volunteers caused a cold and was inactivated by ether which indicated it had a lipid envelope.[23][28] Around the same time, Dorothy Hamre[29] and John Procknow at the University of Chicago isolated a novel cold virus 229E from medical students, which they grew in kidney tissue culture. The novel virus 229E, like the virus strain B814, when inoculated into volunteers caused a cold and was inactivated by ether.[30]

The two novel strains B814 and 229E were subsequently imaged by electron microscopy in 1967 by Scottish virologist June Almeida at St. Thomas Hospital in London.[31][32] Almeida through electron microscopy was able to show that B814 and 229E were morphologically related by their distinctive club-like spikes. Not only were they related with each other, but they were morphologically related to infectious bronchitis virus (IBV).[33] A research group at the National Institute of Health the same year was able to isolate another member of this new group of viruses using organ culture and named the virus strain OC43 (OC for organ culture).[34] Like B814, 229E, and IBV, the novel cold virus OC43 had distinctive club-like spikes when observed with the electron microscope.[35][36]

The IBV-like novel cold viruses were soon shown to be also morphologically related to the mouse hepatitis virus.[18] This new group of IBV-like viruses came to be known as coronaviruses after their distinctive morphological appearance.[10] Human coronavirus 229E and human coronavirus OC43 continued to be studied in subsequent decades.[37][38] The coronavirus strain B814 was lost. It is not known which present human coronavirus it was.[39] Other human coronaviruses have since been identified, including SARS-CoV in 2003, HCoV NL63 in 2004, HCoV HKU1 in 2005, MERS-CoV in 2012, and SARS-CoV-2 in 2019.[40][41] There have also been a large number of animal coronaviruses identified since the 1960s.[5]

Microbiology

Structure

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical, particles with bulbous surface projections.[42] The average diameter of the virus particles is around 125 nm (.125 μm). The diameter of the envelope is 85 nm and the spikes are 20 nm long. The envelope of the virus in electron micrographs appears as a distinct pair of electron-dense shells (shells that are relatively opaque to the electron beam used to scan the virus particle).[43][44]

The viral envelope consists of a lipid bilayer, in which the membrane (M), envelope (E) and spike (S) structural proteins are anchored.[45] The ratio of E:S:M in the lipid bilayer is approximately 1:20:300.[46] On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes.[47] A subset of coronaviruses (specifically the members of betacoronavirus subgroup A) also have a shorter spike-like surface protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE).[5]

The coronavirus surface spikes are homotrimers of the S protein, which is composed of an S1 and S2 subunit. The homotrimeric S protein is a class I fusion protein which mediates the receptor binding and membrane fusion between the virus and host cell. The S1 subunit forms the head of the spike and has the receptor binding domain (RBD). The S2 subunit forms the stem which anchors the spike in the viral envelope and on protease activation enables fusion. The E and M protein are important in forming the viral envelope and maintaining its structural shape.[44]

Inside the envelope, there is the nucleocapsid, which is formed from multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which are bound to the positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome in a continuous beads-on-a-string type conformation.[44][48] The lipid bilayer envelope, membrane proteins, and nucleocapsid protect the virus when it is outside the host cell.[49]

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical, particles with bulbous surface projections.[42] The average diameter of the virus particles is around 125 nm (.125 μm). The diameter of the envelope is 85 nm and the spikes are 20 nm long. The envelope of the virus in electron micrographs appears as a distinct pair of electron-dense shells (shells that are relatively opaque to the electron beam used to scan the virus particle).[43][44]

The viral envelope consists of a lipid bilayer, in which the membrane (M), envelope (E) and spike (S) structural proteins are anchored.[45] The ratio of E:S:M in the lipid bilayer is approximately 1:20:300.[46] On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes.[47] A subset of coronaviruses (specifically the members of betacoronavirus subgroup A) also have a shorter spike-like surface protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE).[5]

The coronavirus surface spikes are homotrimers of the S protein, which is composed of an S1 and S2 subunit. The homotrimeric S protein is a class I fusion protein which mediates the receptor binding and membrane fusion between the virus and host cell. The S1 subunit forms the head of the spike and has the receptor binding domain (RBD). The S2 subunit forms the stem which anchors the spike in the viral envelope and on protease activation enables fusion. The E and M protein are important in forming the viral envelope and maintaining its structural shape.[44]

Inside the envelope, there is the nucleocapsid, which is formed from multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which are bound to the positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome in a continuous beads-on-a-string type conformation.[44][48] The lipid bilayer envelope, membrane proteins, and nucleocapsid protect the virus when it is outside the host cell.[49]

Genome

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The genome size for coronaviruses ranges from 26.4 to 31.7 kilobases.[9] The genome size is one of the largest among RNA viruses. The genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail.[44]

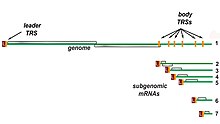

The genome organization for a coronavirus is 5′-leader-UTR-replicase/transcriptase-spike (S)-envelope (E)-membrane (M)-nucleocapsid (N)-3′UTR-poly (A) tail. The open reading frames 1a and 1b, which occupy the first two-thirds of the genome, encode the replicase-transcriptase polyprotein (pp1ab). The replicase-transcriptase polyprotein self cleaves to form 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1–nsp16).[44]

The later reading frames encode the four major structural proteins: spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid.[50] Interspersed between these reading frames are the reading frames for the accessory proteins. The number of accessory proteins and their function is unique depending on the specific coronavirus.[44]

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The genome size for coronaviruses ranges from 26.4 to 31.7 kilobases.[9] The genome size is one of the largest among RNA viruses. The genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail.[44]

The genome organization for a coronavirus is 5′-leader-UTR-replicase/transcriptase-spike (S)-envelope (E)-membrane (M)-nucleocapsid (N)-3′UTR-poly (A) tail. The open reading frames 1a and 1b, which occupy the first two-thirds of the genome, encode the replicase-transcriptase polyprotein (pp1ab). The replicase-transcriptase polyprotein self cleaves to form 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1–nsp16).[44]

The later reading frames encode the four major structural proteins: spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid.[50] Interspersed between these reading frames are the reading frames for the accessory proteins. The number of accessory proteins and their function is unique depending on the specific coronavirus.[44]

Replication cycle

Entry

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a protease of the host cell cleaves and activates the receptor-attached spike protein. Depending on the host cell protease available, cleavage and activation allows the virus to enter the host cell by endocytosis or direct fusion of the viral envelop with the host membrane.[51]

On entry into the host cell, the virus particle is uncoated, and its genome enters the cell cytoplasm.[44] The coronavirus RNA genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail, which allows the RNA to attach to the host cell's ribosome for translation.[44] The host ribosome translates the initial overlapping open reading frame of the virus genome and forms a long polyprotein. The polyprotein has its own proteases which cleave the polyprotein into multiple nonstructural proteins.[44]

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a protease of the host cell cleaves and activates the receptor-attached spike protein. Depending on the host cell protease available, cleavage and activation allows the virus to enter the host cell by endocytosis or direct fusion of the viral envelop with the host membrane.[51]

On entry into the host cell, the virus particle is uncoated, and its genome enters the cell cytoplasm.[44] The coronavirus RNA genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail, which allows the RNA to attach to the host cell's ribosome for translation.[44] The host ribosome translates the initial overlapping open reading frame of the virus genome and forms a long polyprotein. The polyprotein has its own proteases which cleave the polyprotein into multiple nonstructural proteins.[44]

Replicase-transcriptase complex

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). It is directly involved in the replication and transcription of RNA from an RNA strand. The other nonstructural proteins in the complex assist in the replication and transcription process. The exoribonuclease nonstructural protein, for instance, provides extra fidelity to replication by providing a proofreading function which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks.[52]

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). It is directly involved in the replication and transcription of RNA from an RNA strand. The other nonstructural proteins in the complex assist in the replication and transcription process. The exoribonuclease nonstructural protein, for instance, provides extra fidelity to replication by providing a proofreading function which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks.[52]

Replication

One of the main functions of the complex is to replicate the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense genomic RNA from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the replication of positive-sense genomic RNA from the negative-sense genomic RNA.[44]

One of the main functions of the complex is to replicate the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense genomic RNA from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the replication of positive-sense genomic RNA from the negative-sense genomic RNA.[44]

Transcription

The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This process is followed by the transcription of these negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules to their corresponding positive-sense mRNAs.[44] The subgenomic mRNAs form a "nested set" which have a common 5'-head and partially duplicate 3'-end.[53]

The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This process is followed by the transcription of these negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules to their corresponding positive-sense mRNAs.[44] The subgenomic mRNAs form a "nested set" which have a common 5'-head and partially duplicate 3'-end.[53]

Recombination

The replicase-transcriptase complex is also capable of genetic recombination when at least two viral genomes are present in the same infected cell.[53] RNA recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genetic variability within a coronavirus species, the capability of a coronavirus species to jump from one host to another and, infrequently, in determining the emergence of novel coronaviruses.[54] The exact mechanism of recombination in coronaviruses is unclear, but likely involves template switching during genome replication.[54]

The replicase-transcriptase complex is also capable of genetic recombination when at least two viral genomes are present in the same infected cell.[53] RNA recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genetic variability within a coronavirus species, the capability of a coronavirus species to jump from one host to another and, infrequently, in determining the emergence of novel coronaviruses.[54] The exact mechanism of recombination in coronaviruses is unclear, but likely involves template switching during genome replication.[54]

Release

The replicated positive-sense genomic RNA becomes the genome of the progeny viruses. The mRNAs are gene transcripts of the last third of the virus genome after the initial overlapping reading frame. These mRNAs are translated by the host's ribosomes into the structural proteins and a number of accessory proteins.[44] RNA translation occurs inside the endoplasmic reticulum. The viral structural proteins S, E, and M move along the secretory pathway into the Golgi intermediate compartment. There, the M proteins direct most protein-protein interactions required for assembly of viruses following its binding to the nucleocapsid.[55] Progeny viruses are then released from the host cell by exocytosis through secretory vesicles.[55]

The replicated positive-sense genomic RNA becomes the genome of the progeny viruses. The mRNAs are gene transcripts of the last third of the virus genome after the initial overlapping reading frame. These mRNAs are translated by the host's ribosomes into the structural proteins and a number of accessory proteins.[44] RNA translation occurs inside the endoplasmic reticulum. The viral structural proteins S, E, and M move along the secretory pathway into the Golgi intermediate compartment. There, the M proteins direct most protein-protein interactions required for assembly of viruses following its binding to the nucleocapsid.[55] Progeny viruses are then released from the host cell by exocytosis through secretory vesicles.[55]

Transmission

Infected carriers are able to shed viruses into the environment. The interaction of the coronavirus spike protein with its complementary cell receptor is central in determining the tissue tropism, infectivity, and species range of the released virus.[56][57] Coronaviruses mainly target epithelial cells.[5] They are transmitted from one host to another host, depending on the coronavirus species, by either an aerosol, fomite, or fecal-oral route.[58]

Human coronaviruses infect the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, while animal coronaviruses generally infect the epithelial cells of the digestive tract.[5] SARS coronavirus, for example, infects via an aerosol route,[59] the human epithelial cells of the lungs by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.[60] Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) infects, via a fecal-oral route,[58] the pig epithelial cells of the digestive tract by binding to the alanine aminopeptidase (APN) receptor.[44]

Infected carriers are able to shed viruses into the environment. The interaction of the coronavirus spike protein with its complementary cell receptor is central in determining the tissue tropism, infectivity, and species range of the released virus.[56][57] Coronaviruses mainly target epithelial cells.[5] They are transmitted from one host to another host, depending on the coronavirus species, by either an aerosol, fomite, or fecal-oral route.[58]

Human coronaviruses infect the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, while animal coronaviruses generally infect the epithelial cells of the digestive tract.[5] SARS coronavirus, for example, infects via an aerosol route,[59] the human epithelial cells of the lungs by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.[60] Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) infects, via a fecal-oral route,[58] the pig epithelial cells of the digestive tract by binding to the alanine aminopeptidase (APN) receptor.[44]

Classification

The scientific name for coronavirus is Orthocoronavirinae or Coronavirinae.[2][3][4] Coronaviruses belong to the family of Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, and realm Riboviria.[5][6] They are divided into alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses which infect mammals – and gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses, which primarily infect birds.[61][62]- Genus: Alphacoronavirus;[58] type species: Alphacoronavirus 1 (TGEV)

- Genus Betacoronavirus;[59] type species: Murine coronavirus (MHV)

- Species: Betacoronavirus 1 (Bovine Coronavirus, Human coronavirus OC43), Hedgehog coronavirus 1, Human coronavirus HKU1, Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2), Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

- Genus Gammacoronavirus;[17] type species: Avian coronavirus (IBV)

- Genus Deltacoronavirus; type species: Bulbul coronavirus HKU11

- Species: Bulbul coronavirus HKU11, Porcine co

- Genus: Alphacoronavirus;[58] type species: Alphacoronavirus 1 (TGEV)

- Genus Betacoronavirus;[59] type species: Murine coronavirus (MHV)

- Species: Betacoronavirus 1 (Bovine Coronavirus, Human coronavirus OC43), Hedgehog coronavirus 1, Human coronavirus HKU1, Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2), Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

- Genus Gammacoronavirus;[17] type species: Avian coronavirus (IBV)

- Genus Deltacoronavirus; type species: Bulbul coronavirus HKU11

- Species: Bulbul coronavirus HKU11, Porcine co

Origin

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all coronaviruses is estimated to have existed as recently as 8000 BCE, although some models place the common ancestor as far back as 55 million years or more, implying long term coevolution with bat and avian species.[63] The most recent common ancestor of the alphacoronavirus line has been placed at about 2400 BCE, of the betacoronavirus line at 3300 BCE, of the gammacoronavirus line at 2800 BCE, and of the deltacoronavirus line at about 3000 BCE. Bats and birds, as warm-blooded flying vertebrates, are an ideal natural reservoir for the coronavirus gene pool (with bats the reservoir for alphacoronaviruses and betacoronavirus – and birds the reservoir for gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses). The large number and global range of bat and avian species that host viruses has enabled extensive evolution and dissemination of coronaviruses.[64]

Many human coronaviruses have their origin in bats.[65] The human coronavirus NL63 shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (ARCoV.2) between 1190 and 1449 CE.[66] The human coronavirus 229E shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (GhanaGrp1 Bt CoV) between 1686 and 1800 CE.[67] More recently, alpaca coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E diverged sometime before 1960.[68] MERS-CoV emerged in humans from bats through the intermediate host of camels.[69] MERS-CoV, although related to several bat coronavirus species, appears to have diverged from these several centuries ago.[70] The most closely related bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV diverged in 1986.[71] A possible path of evolution of SARS coronavirus and keen bat coronaviruses is that SARS-related coronaviruses coevolved in bats for a long time. The ancestors of SARS-CoV first infected leaf-nose bats of the genus Hipposideridae; subsequently, they spread to horseshoe bats in the species Rhinolophidae, then to civets, and finally to humans.[72][73]

Unlike other betacoronaviruses, bovine coronavirus of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and subgenus Embecovirus is thought to have originated in rodents and not in bats.[65][74] In the 1790s, equine coronavirus diverged from the bovine coronavirus after a cross-species jump.[75] Later in the 1890s, human coronavirus OC43 diverged from bovine coronavirus after another cross-species spillover event.[76][75] It is speculated that the flu pandemic of 1890 may have been caused by this spillover event, and not by the influenza virus, because of the related timing, neurological symptoms, and unknown causative agent of the pandemic.[77] Besides causing respiratory infections, human coronavirus OC43 is also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases.[78] In the 1950s, the human coronavirus OC43 began to diverge into its present genotypes.[79] Phylogentically, mouse hepatitis virus (Murine coronavirus), which infects the mouse's liver and central nervous system,[80] is related to human coronavirus OC43 and bovine coronavirus. Human coronavirus HKU1, like the aforementioned viruses, also has its origins in rodents.[65]

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all coronaviruses is estimated to have existed as recently as 8000 BCE, although some models place the common ancestor as far back as 55 million years or more, implying long term coevolution with bat and avian species.[63] The most recent common ancestor of the alphacoronavirus line has been placed at about 2400 BCE, of the betacoronavirus line at 3300 BCE, of the gammacoronavirus line at 2800 BCE, and of the deltacoronavirus line at about 3000 BCE. Bats and birds, as warm-blooded flying vertebrates, are an ideal natural reservoir for the coronavirus gene pool (with bats the reservoir for alphacoronaviruses and betacoronavirus – and birds the reservoir for gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses). The large number and global range of bat and avian species that host viruses has enabled extensive evolution and dissemination of coronaviruses.[64]

Many human coronaviruses have their origin in bats.[65] The human coronavirus NL63 shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (ARCoV.2) between 1190 and 1449 CE.[66] The human coronavirus 229E shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (GhanaGrp1 Bt CoV) between 1686 and 1800 CE.[67] More recently, alpaca coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E diverged sometime before 1960.[68] MERS-CoV emerged in humans from bats through the intermediate host of camels.[69] MERS-CoV, although related to several bat coronavirus species, appears to have diverged from these several centuries ago.[70] The most closely related bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV diverged in 1986.[71] A possible path of evolution of SARS coronavirus and keen bat coronaviruses is that SARS-related coronaviruses coevolved in bats for a long time. The ancestors of SARS-CoV first infected leaf-nose bats of the genus Hipposideridae; subsequently, they spread to horseshoe bats in the species Rhinolophidae, then to civets, and finally to humans.[72][73]

Unlike other betacoronaviruses, bovine coronavirus of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and subgenus Embecovirus is thought to have originated in rodents and not in bats.[65][74] In the 1790s, equine coronavirus diverged from the bovine coronavirus after a cross-species jump.[75] Later in the 1890s, human coronavirus OC43 diverged from bovine coronavirus after another cross-species spillover event.[76][75] It is speculated that the flu pandemic of 1890 may have been caused by this spillover event, and not by the influenza virus, because of the related timing, neurological symptoms, and unknown causative agent of the pandemic.[77] Besides causing respiratory infections, human coronavirus OC43 is also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases.[78] In the 1950s, the human coronavirus OC43 began to diverge into its present genotypes.[79] Phylogentically, mouse hepatitis virus (Murine coronavirus), which infects the mouse's liver and central nervous system,[80] is related to human coronavirus OC43 and bovine coronavirus. Human coronavirus HKU1, like the aforementioned viruses, also has its origins in rodents.[65]

Infection in humans

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as MERS-CoV, and some are relatively harmless, such as the common cold.[44] Coronaviruses can cause colds with major symptoms, such as fever, and a sore throat from swollen adenoids.[81] Coronaviruses can cause pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia) and bronchitis (either direct viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis).[82] The human coronavirus discovered in 2003, SARS-CoV, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), has a unique pathogenesis because it causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infections.[82]

Six species of human coronaviruses are known, with one species subdivided into two different strains, making seven strains of human coronaviruses altogether. Four of these coronaviruses continually circulate in the human population and produce the generally mild symptoms of the common cold in adults and children worldwide: -OC43, -HKU1, HCoV-229E, -NL63.[83] These coronaviruses cause about 15% of common colds,[84] while 40 to 50% of colds are caused by rhinoviruses.[85] The four mild coronaviruses have a seasonal incidence occurring in the winter months in temperate climates.[86][87] There is no preference towards a particular season in tropical climates.[88]

Four human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are generally mild:

- Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), α-CoV

- Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), α-CoV

Three human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are potentially severe:

- Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), β-CoV

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), β-CoV

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), β-CoV

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as MERS-CoV, and some are relatively harmless, such as the common cold.[44] Coronaviruses can cause colds with major symptoms, such as fever, and a sore throat from swollen adenoids.[81] Coronaviruses can cause pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia) and bronchitis (either direct viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis).[82] The human coronavirus discovered in 2003, SARS-CoV, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), has a unique pathogenesis because it causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infections.[82]

Six species of human coronaviruses are known, with one species subdivided into two different strains, making seven strains of human coronaviruses altogether. Four of these coronaviruses continually circulate in the human population and produce the generally mild symptoms of the common cold in adults and children worldwide: -OC43, -HKU1, HCoV-229E, -NL63.[83] These coronaviruses cause about 15% of common colds,[84] while 40 to 50% of colds are caused by rhinoviruses.[85] The four mild coronaviruses have a seasonal incidence occurring in the winter months in temperate climates.[86][87] There is no preference towards a particular season in tropical climates.[88]

Four human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are generally mild:

- Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), α-CoV

- Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), α-CoV

Three human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are potentially severe:

- Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), β-CoV

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), β-CoV

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), β-CoV

Severe acute respirtory syndrome(SARS)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus called SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV). SARS was first reported in Asia in February 2003. The illness spread to more than two dozen countries in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia before the SARS global outbreak of 2003 was contained.

Since 2004, there have not been any known cases of SARS reported anywhere in the world. The content in this website was developed for the 2003 SARS epidemic. But some guidelines are still being used. Any new SARS updates will be posted on this website.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

Infection in other animals

Coronaviruses have been recognized as causing pathological conditions in veterinary medicine since the 1930s.[18] They infect a range of animals such as swine, cattle, horses, camels, cats, dogs, rodents, birds, bats, and other wildlife.[8] The majority of animal related coronaviruses infect the intestinal tract and are transmitted by a fecal-oral route.[116]

Coronaviruses have been recognized as causing pathological conditions in veterinary medicine since the 1930s.[18] They infect a range of animals such as swine, cattle, horses, camels, cats, dogs, rodents, birds, bats, and other wildlife.[8] The majority of animal related coronaviruses infect the intestinal tract and are transmitted by a fecal-oral route.[116]

Diseases caused

Coronaviruses can infect the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract of mammals and birds. They cause a range of diseases in farm animals and domesticated pets, some of which can be serious and are a threat to the farming industry. In chickens, the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a coronavirus, targets not only the respiratory tract but also the urogenital tract. The virus can spread to different organs throughout the chicken.[117] Economically significant coronaviruses of farm animals include porcine coronavirus (transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus, TGE) and bovine coronavirus, which both result in diarrhea in young animals. Feline coronavirus: two forms, feline enteric coronavirus is a pathogen of minor clinical significance, but spontaneous mutation of this virus can result in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease associated with high mortality. Similarly, there are two types of coronavirus that infect ferrets: Ferret enteric coronavirus causes a gastrointestinal syndrome known as epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE), and a more lethal systemic version of the virus (like FIP in cats) known as ferret systemic coronavirus (FSC).[118] There are two types of canine coronavirus (CCoV), one that causes mild gastrointestinal disease and one that has been found to cause respiratory disease. Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a coronavirus that causes an epidemic murine illness with high mortality, especially among colonies of laboratory mice.[119] Sialodacryoadenitis virus (SDAV) is highly infectious coronavirus of laboratory rats, which can be transmitted between individuals by direct contact and indirectly by aerosol. Acute infections have high morbidity and tropism for the salivary, lachrymal and harderian glands.[120]

A HKU2-related bat coronavirus called swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) causes diarrhea in pigs.[121]

Prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV, MHV had been the best-studied coronavirus both in vivo and in vitro as well as at the molecular level. Some strains of MHV cause a progressive demyelinating encephalitis in mice which has been used as a murine model for multiple sclerosis. Significant research efforts have been focused on elucidating the viral pathogenesis of these animal coronaviruses, especially by virologists interested in veterinary and zoonotic diseases.[122]

Coronaviruses can infect the upper respiratory and gastrointestinal tract of mammals and birds. They cause a range of diseases in farm animals and domesticated pets, some of which can be serious and are a threat to the farming industry. In chickens, the infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a coronavirus, targets not only the respiratory tract but also the urogenital tract. The virus can spread to different organs throughout the chicken.[117] Economically significant coronaviruses of farm animals include porcine coronavirus (transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus, TGE) and bovine coronavirus, which both result in diarrhea in young animals. Feline coronavirus: two forms, feline enteric coronavirus is a pathogen of minor clinical significance, but spontaneous mutation of this virus can result in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease associated with high mortality. Similarly, there are two types of coronavirus that infect ferrets: Ferret enteric coronavirus causes a gastrointestinal syndrome known as epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE), and a more lethal systemic version of the virus (like FIP in cats) known as ferret systemic coronavirus (FSC).[118] There are two types of canine coronavirus (CCoV), one that causes mild gastrointestinal disease and one that has been found to cause respiratory disease. Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a coronavirus that causes an epidemic murine illness with high mortality, especially among colonies of laboratory mice.[119] Sialodacryoadenitis virus (SDAV) is highly infectious coronavirus of laboratory rats, which can be transmitted between individuals by direct contact and indirectly by aerosol. Acute infections have high morbidity and tropism for the salivary, lachrymal and harderian glands.[120]

A HKU2-related bat coronavirus called swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV) causes diarrhea in pigs.[121]

Prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV, MHV had been the best-studied coronavirus both in vivo and in vitro as well as at the molecular level. Some strains of MHV cause a progressive demyelinating encephalitis in mice which has been used as a murine model for multiple sclerosis. Significant research efforts have been focused on elucidating the viral pathogenesis of these animal coronaviruses, especially by virologists interested in veterinary and zoonotic diseases.[122]

Domestic animals

- Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) causes avian infectious bronchitis.

- Porcine coronavirus (transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus of pigs, TGEV).[123][124]

- Bovine coronavirus (BCV), responsible for severe profuse enteritis in of young calves.

- Feline coronavirus (FCoV) causes mild enteritis in cats as well as severe Feline infectious peritonitis (other variants of the same virus).

- the two types of canine coronavirus (CCoV) (one causing enteritis, the other found in respiratory diseases).

- Turkey coronavirus (TCV) causes enteritis in turkeys.

- Ferret enteric coronavirus causes epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets.

- Ferret systemic coronavirus causes FIP-like systemic syndrome in ferrets.[125]

- Pantropic canine coronavirus.

- Rabbit enteric coronavirus causes acute gastrointestinal disease and diarrhea in young European rabbits. Mortality rates are high.[126]

- Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PED or PEDV), has emerged around the world.[127]

- Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) causes avian infectious bronchitis.

- Porcine coronavirus (transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus of pigs, TGEV).[123][124]

- Bovine coronavirus (BCV), responsible for severe profuse enteritis in of young calves.

- Feline coronavirus (FCoV) causes mild enteritis in cats as well as severe Feline infectious peritonitis (other variants of the same virus).

- the two types of canine coronavirus (CCoV) (one causing enteritis, the other found in respiratory diseases).

- Turkey coronavirus (TCV) causes enteritis in turkeys.

- Ferret enteric coronavirus causes epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets.

- Ferret systemic coronavirus causes FIP-like systemic syndrome in ferrets.[125]

- Pantropic canine coronavirus.

- Rabbit enteric coronavirus causes acute gastrointestinal disease and diarrhea in young European rabbits. Mortality rates are high.[126]

- Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PED or PEDV), has emerged around the world.[127]

Good article.

ReplyDeleteQuite informative

ReplyDelete